Modern React testing, part 2: Jest and Enzyme

Enzyme is probably the most popular tool to test React components. And though it has good competition now (see the next article!), it’s still used by many teams.

This is the second article in a series, where we learn how to test React components with Jest and Enzyme and how to apply the best practices we’ve learned in the first article.

- Modern React testing, part 1: best practices

- Modern React testing, part 2: Jest and Enzyme (this post)

- Modern React testing, part 3: Jest and React Testing Library

- Modern React testing, part 4: Cypress and Cypress Testing Library

Getting started with Jest and Enzyme

We’ll set up and use these tools:

Why Jest and Enzyme

Jest has many benefits over other test runners:

- Very fast.

- Interactive watch mode that only runs tests which are relevant to your changes.

- Helpful failure messages.

- Simple configuration, or even zero configuration.

- Mocks and spies.

- Coverage reports.

- Rich matchers API.

Enzyme gives you jQuery-like API to find elements, trigger event handler, and so on. It used to be the de facto tool for testing React components and still very popular. Here I’m not trying to convince you to use Enzyme, but merely sharing my experience with it. We’ll explore a popular alternative, React Testing Library, in the next article in this series.

Some of the Enzyme cons are:

- The API surface is too big, you need to know which methods are good and which are not.

- Too easy to access component internals.

- The API isn’t optimized for modern testing best practices.

Setting up Jest and Enzyme

First, install all the dependencies including peer dependencies:

npm install --save-dev jest react-test-renderer enzyme enzyme-adapter-react-16 node-fetchYou’ll also need babel-jest for Babel and test environment.

Create a src/setupTests.js file to customize the Jest environment:

import Enzyme from 'enzyme';

import Adapter from 'enzyme-adapter-react-16';

// Configure Enzyme with React 16 adapter

Enzyme.configure({ adapter: new Adapter() });

// If you're using the fetch API

import fetch from 'node-fetch';

global.fetch = fetch;Then update your package.json like this:

{

"name": "pizza",

"version": "1.0.0",

"dependencies": {

"react": "16.8.3",

"react-dom": "16.8.3"

},

"devDependencies": {

"enzyme": "3.9.0",

"enzyme-adapter-react-16": "1.11.2",

"jest": "24.6.0",

"node-fetch": "2.6.0",

"react-test-renderer": "16.8.6"

},

"scripts": {

"test": "jest",

"test:watch": "jest --watch",

"test:coverage": "jest --coverage"

},

"jest": {

"setupFilesAfterEnv": ["<rootDir>/src/setupTests.js"]

}

}The setupFilesAfterEnv option tells Jest about our setup file, that we’ve created at the previous step.

Creating our first test

The best location for a test is close to the source code. For example, if you have a component at src/components/Button.js, a test for this component could be at src/components/__tests__/Button.spec.js. Jest will find and run this test automatically.

So, let’s create our first test:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

test('hello world', () => {

const wrapper = mount(<p>Hello Jest!</p>);

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch('Hello Jest!');

});Here we’re rendering a paragraph of text using the Enzyme’s mount() method, then testing that a rendered tree contains “Hello Jest!” text using the Enzyme’s text() method and Jest’s toMatch() assert.

Running tests

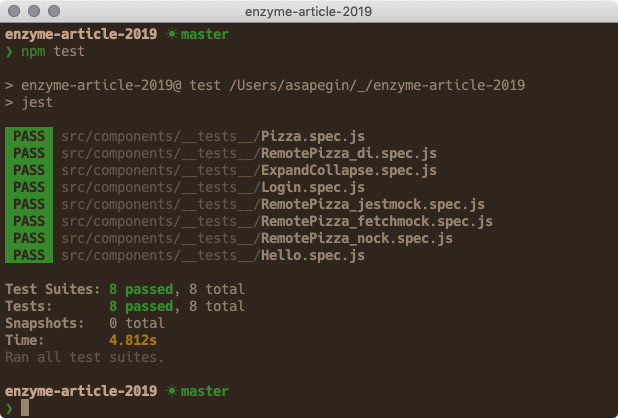

Run npm test (or npm t) to run all tests. You’ll see something like this:

Run npm run test:watch to run Jest in watch mode: Jest will run only tests that are related to files changed since the last commit, and Jest will rerun these test any time you change the code. This is how I usually run Jest. Watch mode is fast enough even in large projects, where running all tests takes many minutes.

Run npm run test:coverage to run all tests and generate coverage report. You can find it in the coverage folder.

mount() vs shallow() vs render()

Enzyme has three rendering methods:

-

mount()renders the whole DOM tree and gives you jQuery-like API to access DOM elements inside this tree, simulate events and read text content. I prefer this method most of the time. -

render()returns a string with rendered HTML code, similar to therenderToString()method fromreact-dom. It’s useful when you need to test HTML output. For example, a component that renders Markdown. -

shallow()renders only the component itself without its children. I never use it. Imagine, you want to click a button in your feature and see that text somewhere changes, but likely both, the button and the text, will be inside children components, so you’ll end up testing internals like props or state, which should be avoided. See Kent C. Dodds’ article Why I never use shallow rendering for more details.

Snapshot testing

Jest snapshots work like this: you tell Jest that you want to be sure that output of this component should never change accidentally and Jest saves your component output, called snapshot, to a file:

exports[`test should render a label 1`] = `

<label

className="isBlock">

Hello Jest!

</label>

`;Every time you, or someone in your team, change your markup Jest will show a diff and ask to update a snapshot if the change was intended.

You can use snapshots to store any values: React tree, strings, numbers, object, etc.

Snapshot testing sounds like a good idea, but has several problems:

- easy to commit snapshots with bugs;

- failures are hard to understand;

- a small change can lead to hundreds of failed snapshots;

- we tend to update snapshots without thinking;

- coupling with low-level modules;

- test intentions are hard to understand;

- they give a false sense of security.

Avoid snapshot testing unless you’re testing very short output with clear intent, like class names or error messages, or when you really want to verify that the output is the same.

If you use snapshots keep them short and prefer toMatchInlineSnapshot() over toMatchSnapshot().

For example, instead of snapshotting the whole component output:

test('shows out of cheese error message', () => {

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza />);

expect(wrapper.debug()).toMatchSnapshot();

});Only snapshot a part you’re testing:

test('shows out of cheese error message', () => {

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza />);

const error = wrapper.find('[data-testid="errorMessage"]').text();

expect(error).toMatchInlineSnapshot(`Error: Out of cheese!`);

});Selecting DOM elements for tests

Generally your tests should resemble how your users interact with your app. That means you should avoid relying on implementation details, because they can change and you’ll need to update your tests.

Let’s compare different methods of selecting DOM elements:

| Selector | Recommended | Notes |

|---|---|---|

button, Button | Never | Worst: too generic |

.btn.btn-large | Never | Bad: coupled to styles |

#main | Never | Bad: avoid IDs in general |

[data-testid="cookButton"] | Sometimes | Okay: not visible to the user, but not an implementation detail, use when better options aren’t available |

[alt="Chuck Norris"], [role="banner"] | Often | Good: still not visible to users, but already part of the app UI |

[children="Cook pizza!"] | Always | Best: visible to the user part of the app UI |

To summarise:

- Prefer queries that rely on information visible to the user, like button labels, or to assistive technologies, like image

altattributes or ARIAroles. - Use

data-testidwhen none of the above works. - Avoid implementation details like HTML element or React component names, CSS class names or IDs.

For example, to select this button in a test:

<button data-testid="cookButton">Cook pizza!</button>We can either query it by its text content:

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza />);

wrapper.find({children: "Cook pizza!"]})Or query it by the test ID:

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza />);

wrapper.find({'data-testid': "cookButton"]})Both are valid, and both have their downsides:

- Text content may change and you’ll need to update your tests. This may not be a problem if your translation library only render string IDs in tests, or if you want your test to work with the actual text users see in the app.

- Test IDs clutter your markup with props you only need in tests. Test IDs are also something that users of your app don’t see: if you remove a label from a button, a test with test ID will still pass. You may want to set up something to remove them from the markup you send to your users.

There’s no single perfect method of selecting elements in tests, but some methods are better than some others.

To simulate() or not

There are two ways to fire an event in Enzyme:

- using

simulate()method, likewrapper.simulate('click'); - calling an event handler prop directly, like

wrapper.props().onClick().

Which method to use is a big debate in the Enzyme community.

The name simulate() is misleading: it doesn’t really simulate an event but calls the prop the same way we’d do it manually. These two lines will do almost the same:

wrapper.simulate('click');

wrapper.props().onClick();There’s one difference when you use Hooks in your components: simulate() will call act() method from Test Utilities to “make your test run closer to how React works in the browser”. You’ll see a warning from React when you call an event handler directly on a component with Hooks.

Most of the time difference between calling an event handler directly (either by calling a prop or with simulate() method) and the real browser behavior isn’t important but in some cases this difference may lead you to misunderstanding of your tests’ behavior. For example, if you simulate() a click on a submit button in a form, it won’t submit the form, like a real submit button would do.

Testing React components

Check out all the examples on CodeSandbox. Unfortunately, CodeSandbox doesn’t fully support Jest and some tests fail there, unless you clone the GitHub repository and run tests locally.

Testing rendering

This kind of test can be useful when your component has several variations and you want to test that a certain prop renders the correct variation.

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import Pizza from '../Pizza';

test('contains all ingredients', () => {

const ingredients = ['bacon', 'tomato', 'mozzarella', 'pineapples'];

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza ingredients={ingredients} />);

ingredients.forEach(ingredient => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(ingredient);

});

});Here we’re testing that our Pizza component renders all ingredients passed to a component as a prop.

Testing user interaction

To “simulate” (see “To simulate() or not” above) an event like click or change, call the simulate method and then test the output:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import ExpandCollapse from '../ExpandCollapse';

test('button expands and collapses the content', () => {

const children = 'Hello world';

const wrapper = mount(

<ExpandCollapse excerpt="Information about dogs">

{children}

</ExpandCollapse>

);

expect(wrapper.text()).not.toMatch(children);

wrapper.find({ children: 'Expand' }).simulate('click');

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(children);

wrapper.update();

wrapper.find({ children: 'Collapse' }).simulate('click');

expect(wrapper.text()).not.toMatch(children);

});Here we have a component that shows some text when you click the “Expand” button and hides it when you click the “Collapse” button. Our test verifies this behavior.

See “Enzyme caveats” section below for more information on the wrapper.update() method.

See the next section for a more complex example of testing events.

Testing event handlers

When you unit test a single component, event handlers are often defined in the parent component, and there are no visible changes as a reaction to these events. They also define the API of a component that you want to test.

jest.fn() creates a mock function, or a spy, that allows you to check how many times it was called and with which parameters.

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import Login from '../Login';

test('submits username and password', () => {

const username = 'me';

const password = 'please';

const onSubmit = jest.fn();

const wrapper = mount(<Login onSubmit={onSubmit} />);

wrapper

.find({ 'data-testid': 'loginForm-username' })

.simulate('change', { target: { value: username } });

wrapper

.find({ 'data-testid': 'loginForm-password' })

.simulate('change', { target: { value: password } });

wrapper.update();

wrapper.find({ 'data-testid': 'loginForm' }).simulate('submit', {

preventDefault: () => {}

});

expect(onSubmit).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(1);

expect(onSubmit).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

username,

password

});

});Here we’re using jest.fn() to define a spy for onSubmit prop of our Login component, then we’re filling the form using a technique, described in the previous section, then we’re calling the onSubmit prop on a <form> element and check that the onSubmit function was called only once and it has received login and password.

Firing a form submit handler directly is not ideal, because it may lead to false positives in our test, but that’s the only way we can submit a form with Enzyme. For example, we can’t test that a submit button actually submits the form. Some people think such tests are testing the browser, not our code, and should be avoided. But they are not: there are many ways you can mess up a submit button, like placing it outside of the form or with type="button".

Async tests

Asynchronous operations are the most tricky to test. Often developers give up and add random delays to their tests:

const wait = (time = 0) =>

new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(resolve, time);

});

test('something async', async () => {

// Run an async operation...

await wait(100).then(() => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch('Done!');

});

});This approach is problematic. The delay will always be a random number. A number that is good enough on a developer’s machine at the time of writing the code. But it can be too long or too short at any other time and on any other machine. When it’s too long, our test will run longer than necessary. When it’s too short, our test will break.

A better approach would be polling: waiting for the desired result, like new text on a page, by checking it multiple times with short intervals, until the expectation is true. The wait-for-expect library does exactly that:

import waitForExpect from 'wait-for-expect';

test('something async', async () => {

expect.assertions(1);

// Run an async operation...

await waitForExpect(() => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch('Done!');

});

});Now our tests will wait as long as necessary but not more.

expect.assertions() method is useful for writing async tests: you tell Jest how many assertions you have in your test, and if you mess up something, like forget to return a Promise from test(), this test will fail.

See the next section for more realistic examples.

Testing network requests and mocks

There are many ways to test components, that send network requests:

- dependency injection;

- mocking a service module;

- mocking a high-level network API, like

fetch; - mocking a low-level network API, that catches all ways of making network requests.

I’m not mentioning sending a real network request to a real API as an option here, because it’s slow and fragile. Every network problem or change of the data, returned by the API, may break our tests. Also, you’ll need to have the right data for all test

Dependency injection is when you pass a dependency as a function parameter or a component prop, instead of hardcoding it inside a module. This allows you to pass another implementation in a test. Use default function parameters or default component props to define the default implementation, one that should be used in non-test code. That way you won’t have to pass the dependency every time you use a function or a component:

import React from 'react';

const defaultFetchIngredients = () => fetch(URL).then(r => r.json());

export default function RemotePizza({ fetchIngredients }) {

const [ingredients, setIngredients] = React.useState([]);

const handleCook = () => {

fetchIngredients().then(response => {

setIngredients(response.args.ingredients);

});

};

return (

<>

<button onClick={handleCook}>Cook</button>

{ingredients.length > 0 && (

<ul>

{ingredients.map(ingredient => (

<li key={ingredient}>{ingredient}</li>

))}

</ul>

)}

</>

);

}

RemotePizza.defaultProps = {

fetchIngredients: defaultFetchIngredients

};When we use our component without passing the fetchIngredients prop, it’ll use the default implementation:

<RemotePizza />But in tests we’ll pass a custom implementation, that returns mock data instead of making an actual network request:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import { act } from 'react-dom/test-utils';

import waitForExpect from 'wait-for-expect';

import RemotePizza from '../RemotePizza';

const ingredients = ['bacon', 'tomato', 'mozzarella', 'pineapples'];

test('download ingredients from internets', async () => {

expect.assertions(4);

const fetchIngredients = () =>

Promise.resolve({

args: { ingredients }

});

const wrapper = mount(

<RemotePizza fetchIngredients={fetchIngredients} />

);

await act(async () => {

wrapper.find({ children: 'Cook' }).simulate('click');

});

await waitForExpect(() => {

wrapper.update();

ingredients.forEach(ingredient => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(ingredient);

});

});

});Note that we’re wrapping async operations in the act() method here.

Dependency injection is great for unit tests, when you’re rendering a component that accepts an injection directly, but for integration tests need too much boilerplate to pass dependencies to deeply nested components.

That’s where request mocking comes in.

Mocking is similar to dependency injection in a way that you’re also replacing a dependency implementation with your own in a test, but it works on a deeper level: by modifying how either module loading or browser APIs, like fetch, work.

With jest.mock() you can mock any JavaScript module. To make it work in our case, we need to extract our fetching function to a separate module, often called a service module:

export const fetchIngredients = () =>

fetch(

'https://httpbin.org/anything?ingredients=bacon&ingredients=mozzarella&ingredients=pineapples'

).then(r => r.json());Then import it in a component:

import React from 'react';

import { fetchIngredients } from '../services';

export default function RemotePizza() {

/* Same as above */

}And now we can mock it in our test:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import { act } from 'react-dom/test-utils';

import waitForExpect from 'wait-for-expect';

import RemotePizza from '../RemotePizza';

import { fetchIngredients } from '../../services';

jest.mock('../../services');

afterEach(() => {

fetchIngredients.mockReset();

});

const ingredients = ['bacon', 'tomato', 'mozzarella', 'pineapples'];

test('download ingredients from internets', async () => {

expect.assertions(4);

fetchIngredients.mockResolvedValue({ args: { ingredients } });

const wrapper = mount(<RemotePizza />);

await act(async () => {

wrapper.find({ children: 'Cook' }).simulate('click');

});

await waitForExpect(() => {

wrapper.update();

ingredients.forEach(ingredient => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(ingredient);

});

});

});We’re using Jest’s mockResolvedValue method to resolve a Promise with a mock data.

Mocking the fetch API is similar to mocking a method, but instead of importing a method and mocking it with jest.mock(), you’re matching a URL and giving a mock response.

We’ll use fetch-mock to mock the API request:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import fetchMock from 'fetch-mock';

import { act } from 'react-dom/test-utils';

import waitForExpect from 'wait-for-expect';

import RemotePizza from '../RemotePizza';

const ingredients = ['bacon', 'tomato', 'mozzarella', 'pineapples'];

afterAll(() => {

fetchMock.restore();

});

test('download ingredients from internets', async () => {

expect.assertions(4);

fetchMock.restore().mock(/https:\/\/httpbin.org\/anything\?.*/, {

body: { args: { ingredients } }

});

const wrapper = mount(<RemotePizza />);

await act(async () => {

wrapper.find({ children: 'Cook' }).simulate('click');

});

await waitForExpect(() => {

wrapper.update();

ingredients.forEach(ingredient => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(ingredient);

});

});

});Here we’re using mock() method from fetch-mock to return a mock response to any network request matching the given URL pattern. The rest of the test is the same as with dependency injection.

Mocking the network is similar to mocking fetch API but it works on a lower level, so network requests, sent using other APIs, like XMLHttpRequest, will also be mocked.

We’ll use Nock to mock the network request:

import React from 'react';

import { mount } from 'enzyme';

import nock from 'nock';

import { act } from 'react-dom/test-utils';

import waitForExpect from 'wait-for-expect';

import RemotePizza from '../RemotePizza';

const ingredients = ['bacon', 'tomato', 'mozzarella', 'pineapples'];

afterEach(() => {

nock.restore();

});

test('download ingredients from internets', async () => {

expect.assertions(5);

const scope = nock('https://httpbin.org')

.get('/anything')

.query(true)

.reply(200, { args: { ingredients } });

const wrapper = mount(<RemotePizza />);

await act(async () => {

wrapper.find({ children: 'Cook' }).simulate('click');

});

await waitForExpect(() => {

wrapper.update();

expect(scope.isDone()).toBe(true);

ingredients.forEach(ingredient => {

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch(ingredient);

});

});

});The code is almost the same as with fetch-mock, but here we’re defining a scope: a mapping of request URLs and mock responses.

query(true) means we’re matching a request with any query parameters, otherwise you can define a specific parameters, like query({quantity: 42}).

scope.isDone() is true when all requests, defined in the scope, were made.

I’d choose between jest.mock() and Nock:

jest.mock()is already available with Jest and you don’t need to set up and learn anythingnew — it works the same way as mocking any other modules.- Nock has slightly more convenient API than fetch-mock, and debugging tools. It can also record real network request, so you don’t have to hand-craft mock responses.

Enzyme caveats

update() method

Enzyme’s update() is a magical thing. That’s how the docs describe it:

Forces a

re-render . Useful to run before checking the render output if something external may be updating the state of the component somewhere.

Someone doing something somewhere. I couldn’t find any logic on when you need to use it. So my rule of thumb is: write tests without it until you see stale render output. Then add update() before your expect().

Note, that you can only call update() on the wrapper instance:

const wrapper = mount(<Pizza />);

// Someone doing something somewhere...

wrapper.update();

expect(wrapper.text()).toMatch('wow much updates');hostNodes() method

Imagine you have a button component:

const Button = props => <button className="Button" {...props} />;You have a form:

<form>

<Button data-testid="pizzaForm-submit">Cook pizza!</Button>

</form>And you try to simulate a click on this button in your test:

wrapper.find('[data-testid="pizzaForm-submit"]').simulate('click');This won’t work because find() returns two nodes: one for the Button React component, and one for the button HTML element, because the component tree would look like this:

<Button data-testid="pizzaForm-submit">

<button className="Button" data-testid="pizzaForm-submit">

Cook pizza!

</button>

</Button>To avoid that, you need to use the Enzyme’s hostNodes() method:

wrapper

.find('[data-testid="pizzaForm-submit"]')

.hostNodes()

.simulate('click');hostNodes() method returns only host nodes: in React DOM host nodes are HTML elements.

Reusing find() queries

Be careful with caching and reusing find() queries in your test like so:

const input = wrapper.find('[data-testid="quantity"]');

expect(input.prop('value')).toBe('0'); // -> PassIt will fail if you change the input’s value and try to reuse the input variable to test it:

input.simulate('change', { target: { value: '42' } });

expect(input.prop('value')).toBe('42'); // -> Fail!

expect(input.prop('value')).toBe('0'); // -> PassThis happens because the input variable still keeps the reference to the initial component tree.

To fix this we need to run the find() query again after we change input’s value:

const findInput = wrapper => wrapper.find('[data-testid="quantity"]');

expect(findInput(wrapper).prop('value')).toBe('0'); // -> Pass

findInput(wrapper).simulate('change', { target: { value: '42' } });

expect(findInput(wrapper).prop('value')).toBe('42'); // -> PassI usually don’t reuse any queries in my tests, and write little helper functions, like the findInput above, instead. This saves me a lot of debugging time.

act() helper

Wrap “units” of interaction, like rendering, user events, or data fetching, with the act() method from React Test Utilities to make your tests better resemble how your users will interact with your app.

Enzyme calls the act() method for you in some of its methods, like simulate(), but in some cases you need to use it manually in your tests.

Testing recipes page has a better explanation of the act() method and more examples of its usage.

Debugging

Sometimes you want to check the rendered React tree, use the debug() method:

const wrapper = mount(<p>Hello Jest!</p>);

console.log('LOL', wrapper.debug());

// -> <p>Hello Jest!</p>You can also print an element:

console.log('LOL', wrapper.find({ children: 'Expand' }).debug());Conclusion

We’ve learned how to set up Enzyme and how to test different React components.

In the next article we’ll look at React Testing Library and how it compares to Enzyme.

Thanks to Joe Boyle, Kent C. Dodds, Anna Gerus, Patrick Hund, Monica Lent, Morgan Packard, Alexander Plavinski, Giorgio Polvara, Juho Vepsäläinen.