A rebel’s guide to pull requests, commits, and code reviews

I happened to have a somewhat controversial approach to pull requests. This approach has worked well for me for many years, and my colleagues seem to be happy with it. However, many would consider these practices

I’ve written before on getting code reviewed faster and have published a frontend pull request checklist — check them out!

Story time I once broke a deployment tool by adding an emoji into a commit message, and I still consider this a tiny victory in my programming career. Funnily, my colleagues split into two camps after this incident. The first camp was saying that I’m an idiot to use emojis in commit messages, and the

Don’t bother with atomic commits

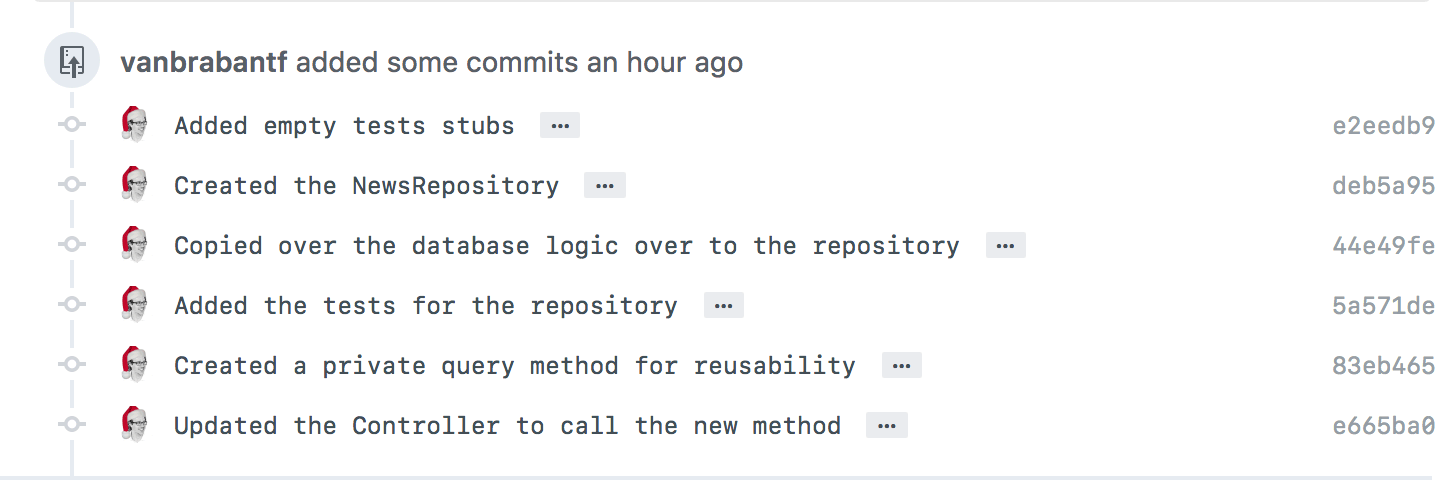

Some folks prefer to check the changes in a pull request as a whole, some prefer to check each commit separately. The latter explains that they want to understand the thought process of a developer, and they prefer to look at smaller changes, and how a developer came up with the solution.

This approach is called atomic commits, meaning a bigger change is split into multiple smaller independentish changes, and each is represented as a separate commit with a meaningful description of a change.

(An illustration from Frederick Vanbrabant’s article.)

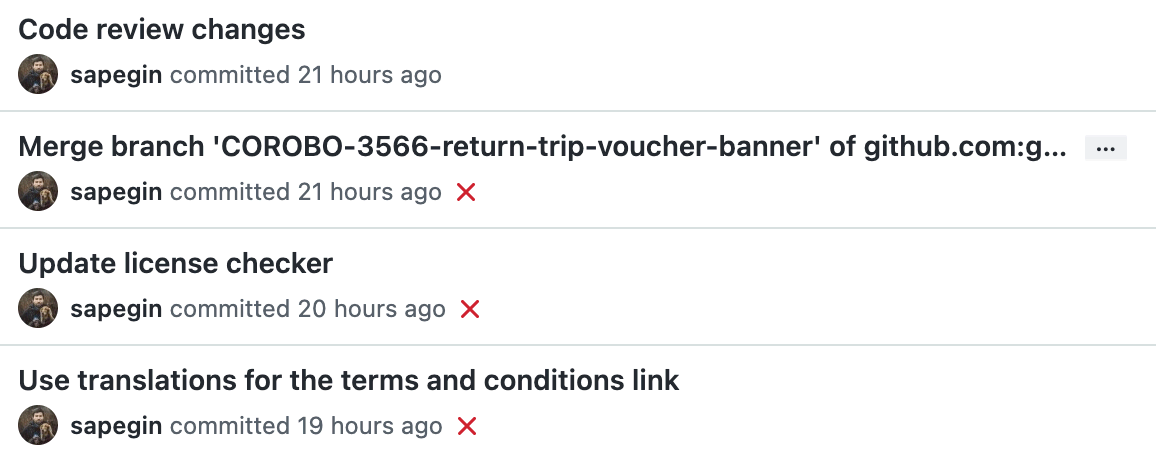

Some even go further and want each change requested during code review to be in a separate commit.

I always review the whole pull request because I don’t want to review tiny changes but the state of the codebase after the change. Small changes may look okay independently but in the end, they may produce messy code, duplication, or inconsistencies with already existing

Atomic commits read like a novel, taking us behind the scenes of a pull request, and it takes a lot of time to write and maintain them. I’d prefer developers to spend this energy on writing great and helpful pull request descriptions.

If some of the changes need additional explanation, code or pull request comments are better places for

Also, atomic commits will likely require rewriting commit history and

I only use atomic commits after the first code review iteration, so reviewers could better see what was changed since the last review. And still, if the changes are minor, I’d group them into a single commit.

And if the pull request is too big to review, or contains unrelated changes like refactoring or bugfixes, we should split it into several pull requests.

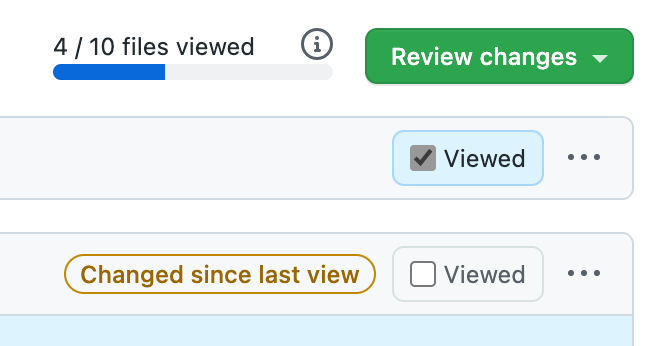

Tip To avoid reviewing the same code on each iteration, mark files as reviewed on GitHub, and they will stay collapsed until the author changes anything inside them.

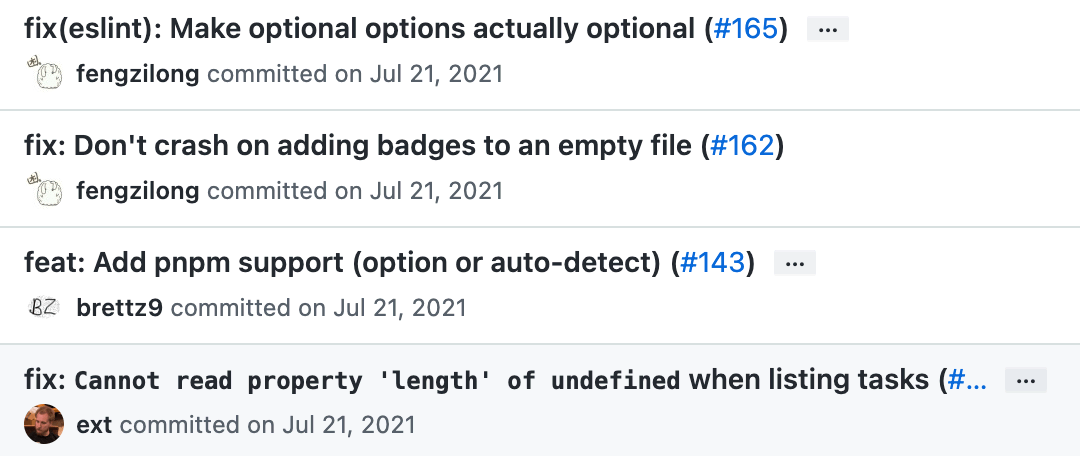

Squash-merge pull requests

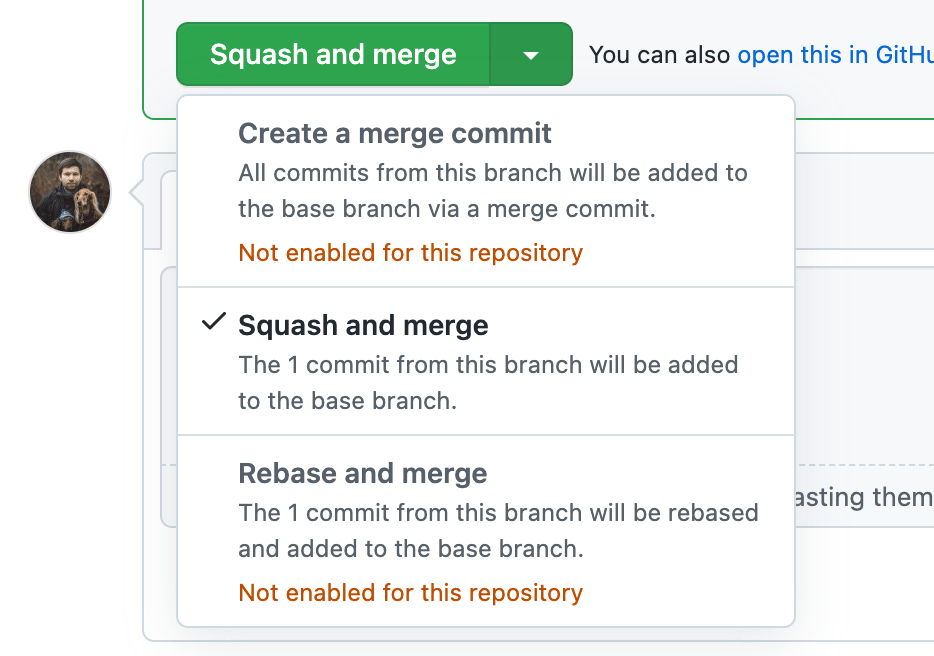

When I merge pull requests, I always squash all commits into a single commit, and edit the commit message to describe the whole change.

This has several benefits:

- Clean and readable project history developers merge dozens or even hundreds of pull requests every day on a typical project, keeping each commit will make the history enormous and unusable. Also, commit messages will be too low-level to be useful.

- No time wasted on managing commits inside a pull request discard all the separate commits, so developers don’t have to bother keeping the branch history clean and force pushing.

- Easier debugging each commit corresponds to a pull request, so once we find where the bug was introduced, we know which pull request is responsible for it.

- Easier reverts we revert a complete feature, so the author could fix it, retest, and submit it as a new pull request. Reverting a whole pull request brings the project back to a previous known working state, reverting atomic commits will have unpredictable consequences, and likely break something.

Tip Allow only squash merging on GitHub, and aisable other merge types. Also, disable force pushing to prevent various problems, like overwriting someone else’s work.

It’s easier and safer to treat pull requests as atomic changes, meaning we merge a pull request as a single commit (a single item in the project history), and we revert a pull request completely if something goes wrong.

Merge commits in pull requests are fine

Rebasing a feature branch with the recent changes in the main branch is such a big

Merging the main branch into a feature branch is significantly faster, easier, and less error-prone. Squashing commits while merging a pull request keeps the project history clean, so we’ll only see these merge commints on the pull request page.

Tip I have a Git alias git mmm (“merge master motherfucker”) that fetched the fresh main branch and merges it into my current working branch. I also use git-friendly scripts for pulling, pushing and working with branches and stashes.

Conclusion

The overall quality of a pull request is much more important than the quality of each commit in it. A clear description of what was changed and why, screenshots of any UI changes, and so on. Discarding individual commits while merging a pull request saves time, makes debugging and reverting easier, and avoid issues. Less stress and more time to work on something useful for your colleagues.

And don’t forget to put some emojis in your commit messages once in a

Thanks to Margarita Diaz.